Over the past thirteen years, Nigeria’s higher education system has received more than ₦1.5 trillion through the Tertiary Education Trust Fund. That kind of money should have transformed our universities, polytechnics, and colleges of education into stronger, better-equipped institutions.

But if you walk across many campuses today, the reality tells a different story. The impact on daily campus life is harder to see. Students and lecturers still struggle in environments that fall short of the investment made.

This piece tracks how the money was shared, what it was meant to achieve, and why results are still missing on many campuses. It shows how opacity and weak oversight have slowed the transformation TETFund was created to deliver.

How TETFund Allocations Were Shared

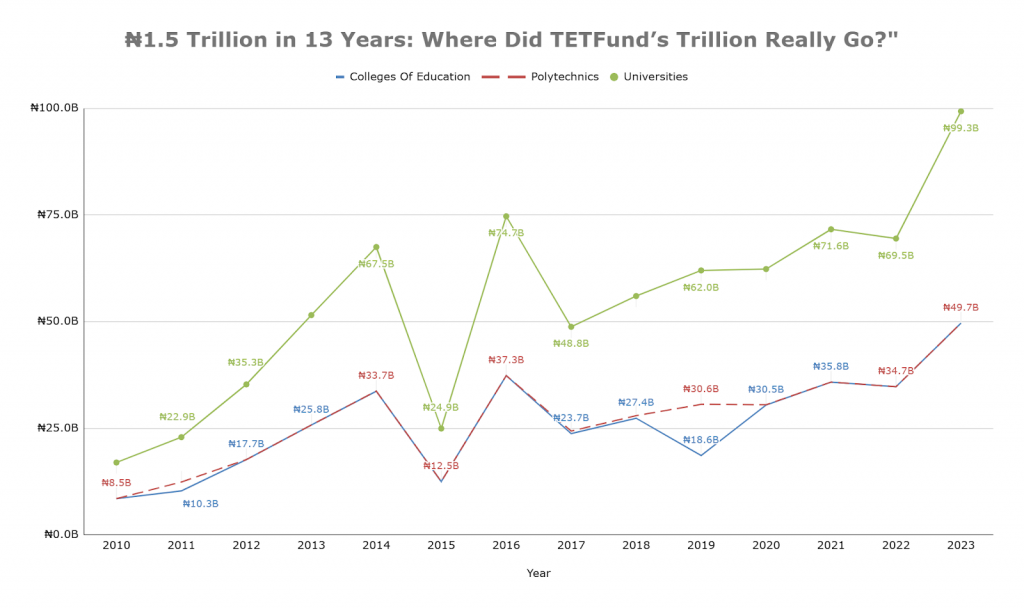

Of the ₦1.5 trillion disbursed between 2010 and 2023, universities always took the largest share. In 2023, they received ₦99.3 billion, while polytechnics and colleges of education got ₦49.7 billion each. Within each group, every institution received the same amount.

Fig 1: Total annual spend by institution type, 2010-2023

This came to about ₦10.2 billion per university and between ₦300 million and ₦700 million a year for most polytechnics and colleges.

Funding did not rise in a straight line. The sharpest drop came in 2015, when allocations crashed across the board. The cut reflected both a change in government and a collapse in oil prices that pushed Nigeria into recession.

Spending began to climb again from 2017, largely financed by debt. After 2020, the government expanded budgets further during the pandemic, and by 2023 allocations were at record highs.

Bigger numbers, however, did not always mean stronger campuses.

What TETFund Money Was Meant to Achieve

The largest share of TETFund allocations went to infrastructure. That covered new lecture halls, renovated hostels, upgraded labs, and libraries.

It also included project maintenance and the creation of entrepreneurship centers on some campuses. The idea was to make learning environments more functional and modern.

Other categories received smaller but steady funding. These included staff training, academic conferences, institution-based research, journal publications, and manuscript development.

On paper, the distribution looks balanced.

Infrastructure absorbs the most because it is the most urgent. Training and research get less but still matter. The problem comes when the balance between budgets and outcomes is compared.

Despite ₦4.8 billion per university going to infrastructure, many lecture halls are still dilapidated, hostels remain overcrowded, and labs are poorly equipped.

The gap between what was budgeted and what students actually experience suggests that the challenge is not only about how much was allocated but how projects were tracked and delivered.

How Students Describe Campus Life

Numbers tell part of the story, but life on campus shows another side. In our report, students across several universities described conditions that do not match the scale of TETFund spending.

At Lagos State University, students recalled how lecture halls in the Faculty of Arts were so overcrowded that more than 1,500 people squeezed into spaces designed for half that number. New lecture halls were eventually built between 2020 and 2023, which eased the pressure, but hostels remained a bigger problem.

For over a decade there were none on campus. When a new hostel opened in 2023, it was reserved only for first-year students and was not funded by TETFund.

Faculty of Arts’ lecture hall, Lagos State University (LASU), Ojo, Aug 1st, 2025

At the University of Ibadan, students described hostels as some of the worst in the country. Rooms were cramped and lacked reliable water and electricity. Some reported flooding during heavy rains, while others recalled armed robberies.

Even privately run hostels on campus struggled with poor facilities. Lecture halls saw some renovations supported by TETFund, but accommodation was left behind.

Faculty of Law Lecture Theatre, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, August 20, 2025

Students at Obafemi Awolowo University reported a mix of progress and neglect. In 2023, five new hostels were completed through TETFund, providing some relief. But older hostels such as Fajuyi and Awolowo continued to struggle with water supply despite renovations.

Students also noted two new lecture halls under construction in the Faculty of Arts, along with a new university gate.

At Olabisi Onabanjo University, students described their hostels as poorly built and unhygienic, with unreliable water and electricity. Many chose to live off campus, though the cost was higher. Classrooms were also described as unconducive for learning, with little visible evidence of TETFund projects during their time there.

Taken together, these accounts show that while some projects have been completed, many students still live and learn in environments far removed from what ₦10.2 billion per university should deliver.

Why the Impact of TETFund Remains Limited

TETFund publishes how much each institution receives and what the money is meant to cover. What is harder to trace is what actually happens after disbursement. Three issues come up repeatedly.

First, there is little public record that links allocations to finished projects. A university may receive hundreds of millions for infrastructure, but the trail often ends at the budget line. Second, there is no consistent reporting on outcomes. We know which projects were funded, but not whether they were delivered in full, abandoned midway, or maintained over time. Third, the lack of visible results erodes trust. Students hear about the large figures but do not see changes that match.

The effect is a widening gap between investment and impact. Budgets are visible on paper, but the results are difficult to verify on the ground.

Money Alone Won’t Fix Nigerian Universities

More money does not automatically lead to better universities. When funds are released without strong oversight or transparency, projects stall, fade, or never appear at all.

Infrastructure is the most visible line item, yet it is also where the gap between funding and outcomes is widest. Research and innovation, which receive far smaller allocations, remain chronically underfunded.

The result is a system where students and staff continue to work in poor conditions despite years of rising investment. If disbursement keeps outpacing delivery, students will keep paying the price.

This article draws from our report titled ₦1.5 Trillion in 13 Years: Where Did TETFund’s Billions Really Go?, a fuller investigation with charts, figures, and student accounts.

Johnson is a Content Strategist at Column. He helps brands craft content that drives visibility and results. He studied Economics at the University of Ibadan and brings over years of experience in direct response marketing, combining strategy, creativity, and data-backed thinking.

Connect with him on LinkedIn.