1. Executive summary

We analyzed 129 microgrant‑funded projects supported by the Unitary Foundation between 2018 and 2025 to understand how early‑stage quantum work is actually being built. This isn’t a picture of the entire quantum industry, but a view into the layer where individuals and small teams experiment, write foundational software, build learning pathways, and test ideas that larger funding structures usually don’t touch.

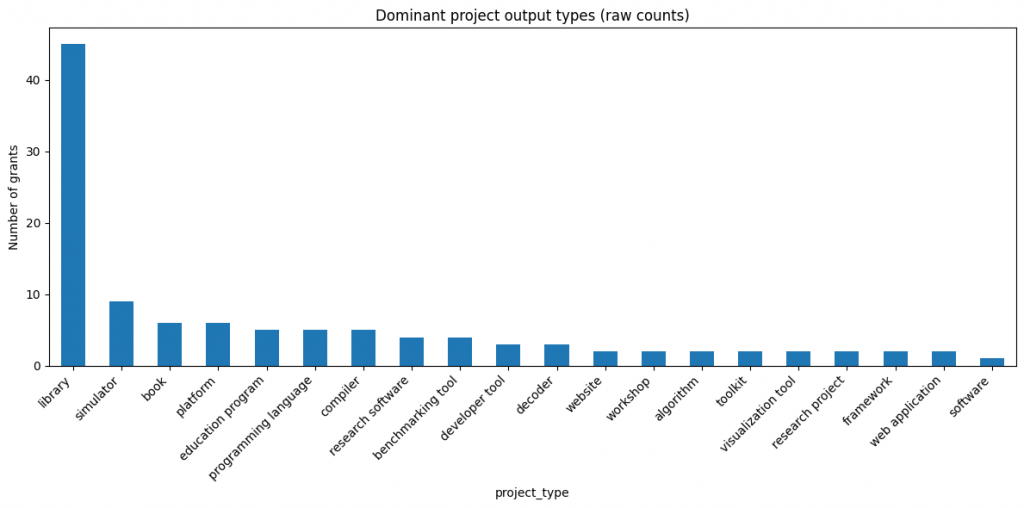

The portfolio is strongly infrastructure‑led. 82.2% of all projects focus on tooling, libraries, simulators, compilers, benchmarking systems, and research frameworks. Education accounts for 17.8%. Libraries alone make up 34.9% of all outputs, showing how heavily the ecosystem invests in reusable technical primitives. Most work is carried by very small teams. Median team size is one or two people across almost all output types, which means progress is coming from accumulation, not coordination.

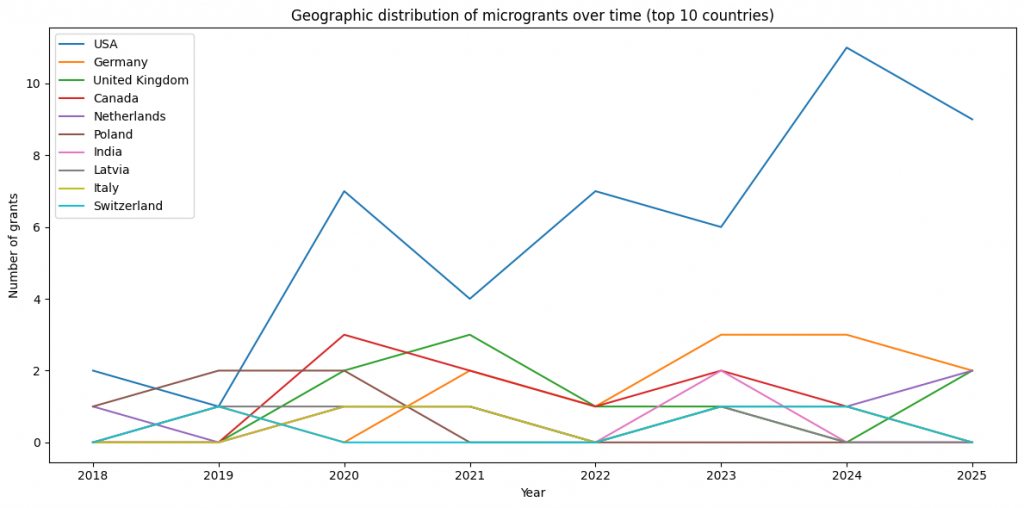

Geographically, activity is concentrated. The United States holds 36.4% of all projects. Germany, the United Kingdom, Canada, and the Netherlands together bring the top five countries to 65.1% of the total. More than twenty other countries share the remaining 34.9%, often through single or intermittent contributions. That tells us where this microgrant model currently finds sustained participation, not where quantum research capacity exists globally.

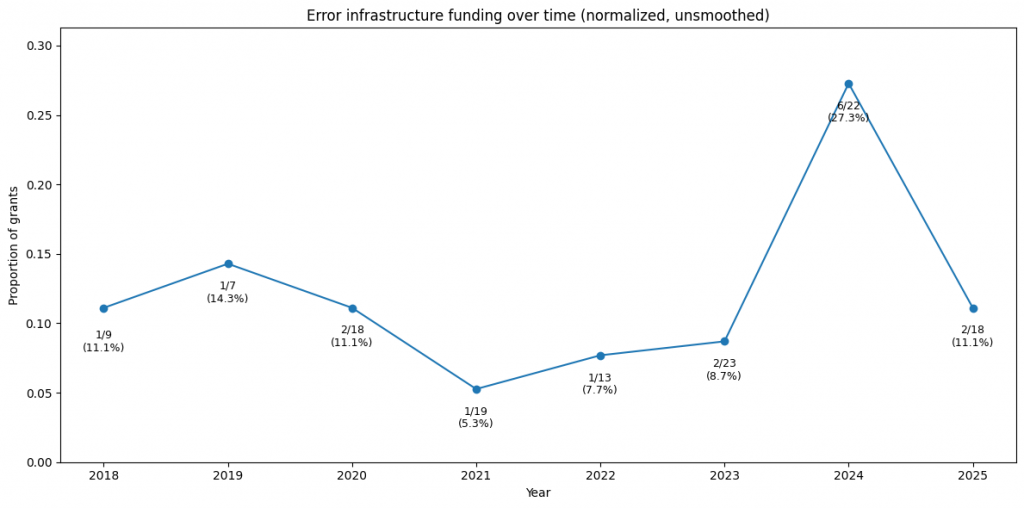

Technically, the work clusters around making quantum systems usable. Simulation (13.2%), software tooling (12.4%), error correction (9.3%), algorithms (7.0%), compilation (5.4%), and optimization (5.4%) form an engineering stack that supports experimentation and reliability. Error infrastructure appears every year but rarely exceeds 15% of projects, except in 2024, where it rises to 27.3%. Reliability is present, but it isn’t yet the center of gravity.

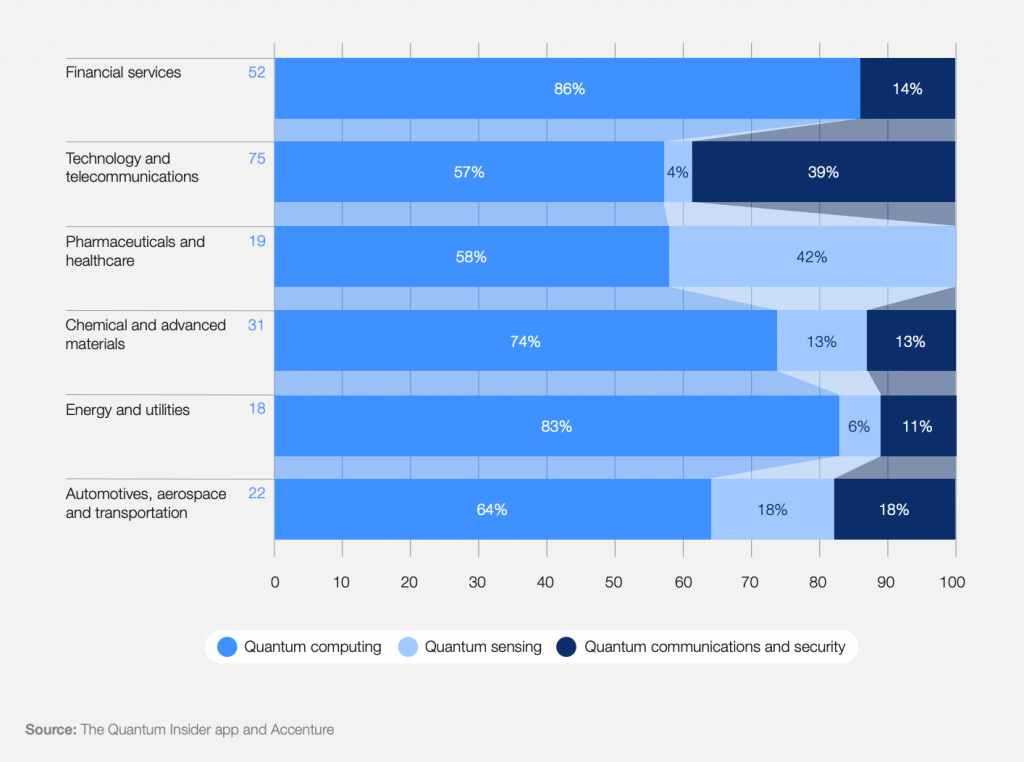

Interdisciplinary work is still thin. Machine learning appears in eight projects, while cryptography and medical imaging appear twice each, and finance only once. This is striking given that industry projections place finance among the largest future application areas for quantum computing. The gap points to a need for more targeted funding, not a lack of relevance.

What this dataset shows is an ecosystem being built carefully and cheaply compared to the cost of quantum hardware itself. A large share of structural progress is happening through small grants and independent builders. It means companies, foundations, and institutions can accelerate real progress with relatively modest capital by funding microgrants, education, and applied crossover work.

If we want faster development in 2026 and beyond, we don’t need fewer experiments. We need more of them, spread across more domains, supported by stronger education pipelines, and connected more directly to industry problems. Microgrants already work. Expanding their reach is one of the most efficient ways to widen participation, deepen infrastructure, and grow the next generation of quantum researchers and engineers.

2. Size, scope, and limitations of the report

This report is based on the 129 microgrant-funded projects supported by the Unitary Foundation between 2018 and 2025. Microgrants sit at the exploratory edge of technical work, funding small, early, and often unfinished ideas. They capture behavior that larger grants usually miss: individual experimentation, narrow tooling, educational scaffolding, and fast iteration.

At the same time, the patterns that follow describe the structure of one program, not universal laws of quantum development. Geographic concentration reflects where applicants and contributors are active in this fund, not global research capacity. Category dominance reflects what people submit and what the fund supports, not what the entire field prioritizes.

The strength of the dataset lies in its consistency. Over eight years, it records how small-scale technical work accumulates, making it valuable as an ecosystem signal. On average, this represents about 16 projects per year. The annual distribution is uneven, with some years supporting fewer than 10 projects and others exceeding 20.

Infrastructure projects account for 106 out of 129 grants, or 82.2%. Education projects (books, workshops, etc.) account for 23 grants, or 17.8%. Software libraries dominate output type at 45 projects in total, or 34.9% of the entire dataset. Simulators follow with 9 projects (7%). Platforms, books, compilers, programming languages, and education programs each fall between 5 and 6 projects, roughly 4–5% per category. All remaining output types sit at or below 3%.

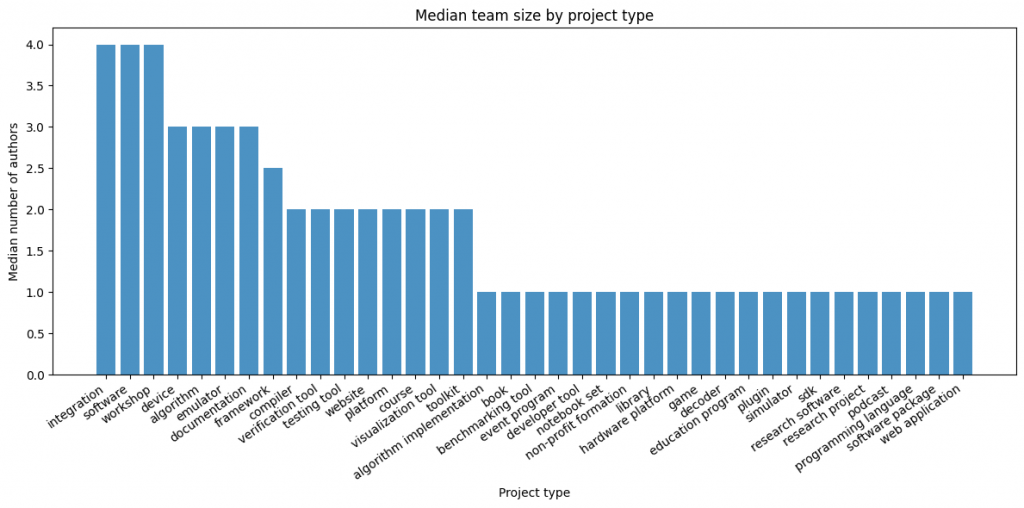

Median team size across nearly all output types is one or two contributors. Workshops and integration projects reach a median of four, but are exceptions.

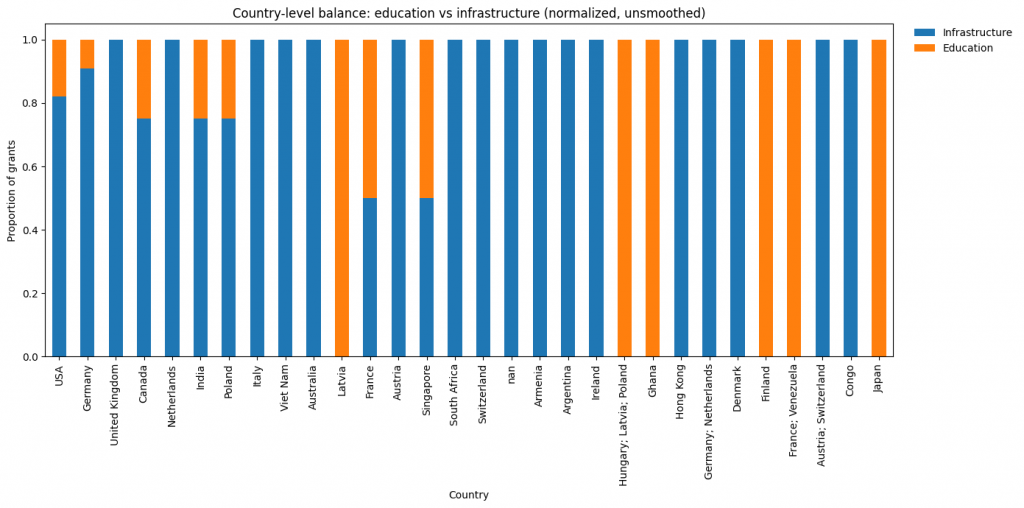

3. Geographic distribution in quantum computing project funding

The United States holds 47 of the 129 projects, representing 36.4% of the entire portfolio. Germany follows with 12 projects (9.3%). Canada and the United Kingdom each have 9 projects (6.97% each). The Netherlands has 7 projects (5.4%).

Top 5 countries leading quantum computing projects (Unitary Fund, 2018-2025)

| Country | Number of projects |

| USA | 47 |

| Germany | 12 |

| United Kingdom | 9 |

| Canada | 9 |

| Netherlands | 7 |

Together, these five countries account for 84 projects, or 65.1% of all microgrants. The remaining 45 projects, or 34.9%, are spread across more than twenty countries. Many of these appear only once or twice in the entire dataset.

This creates a sharp core–periphery structure. A small group of countries participates consistently, while a much larger group participates intermittently.

The United States also shows the strongest growth over time, peaking at 11 grants in 2024. European countries such as Germany, the UK, and the Netherlands show steadier involvement without strong acceleration.

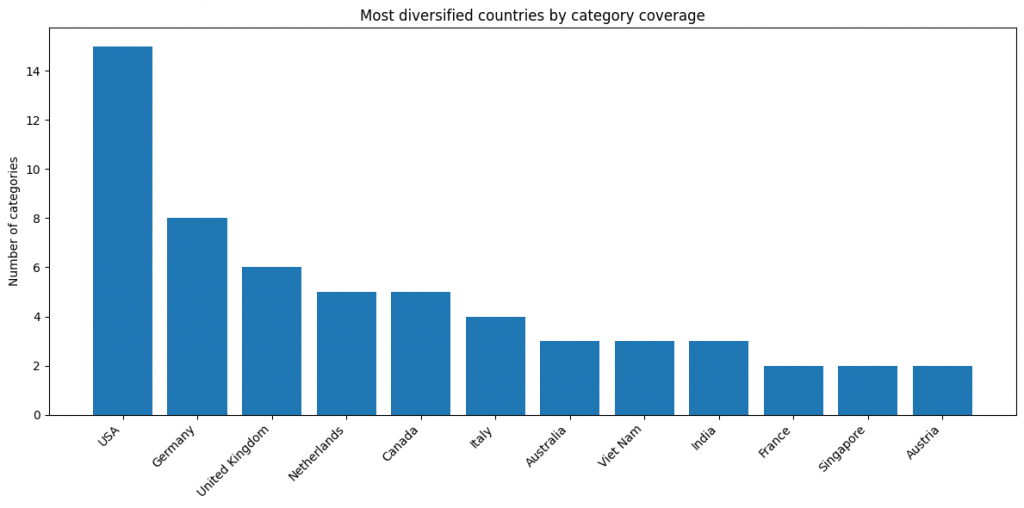

The United States also spans the widest range of categories, covering most of the available category space. This may reflect a broad funding scope, but it can also be driven by higher project volume and the way categories were defined and sampled (or selected by the fund).

Germany and the United Kingdom follow with strong but narrower coverage. Countries like the Netherlands, Canada, and Italy show moderate diversification, while most others concentrate on a small number of categories.

This pattern shouldn’t be read as a global ranking of quantum capability, but as a reflection of where this particular microgrant program has active applicants and recurring contributors.

4. Technical categories

The fund’s projects fall into a small number of dominant categories.

| Category | Projects | Share of total |

| Quantum education | 23 | 17.8% |

| Quantum simulation | 17 | 13.2% |

| Quantum software tooling | 16 | 12.4% |

| Quantum error correction | 12 | 9.3% |

| Quantum algorithms | 9 | 7.0% |

| Quantum optimization | 7 | 5.4% |

| Quantum compilation | 7 | 5.4% |

| Quantum machine learning | 6 | 4.7% |

| Quantum control | 5 | 3.9% |

| Quantum tomography | 4 | 3.1% |

Education is the largest super-category, but engineering‑adjacent work dominates collectively. Simulation, tooling, error correction, algorithms, compilation, and optimization together account for 52.7% of the entire portfolio.

This composition describes a field focused on making quantum systems usable. Simulation supports experimentation, tooling reduces friction, error correction addresses reliability, and algorithms define computational capability. Compilation and optimization link abstract models to hardware constraints.

The portfolio behaves like an engineering stack being assembled from the bottom up, with each category supplying a different layer.

5. Infrastructure versus education in quantum computing

Advanced research environments rely on both education and infrastructure. One expands the pool of people who can participate, while the other determines what those people can build. This dataset shows how effort is distributed between the two within a single funding stream.

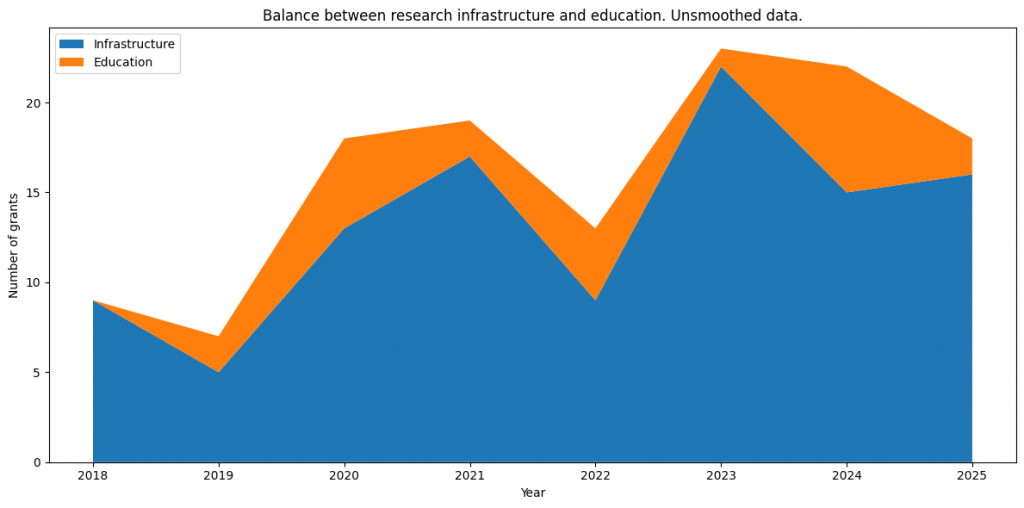

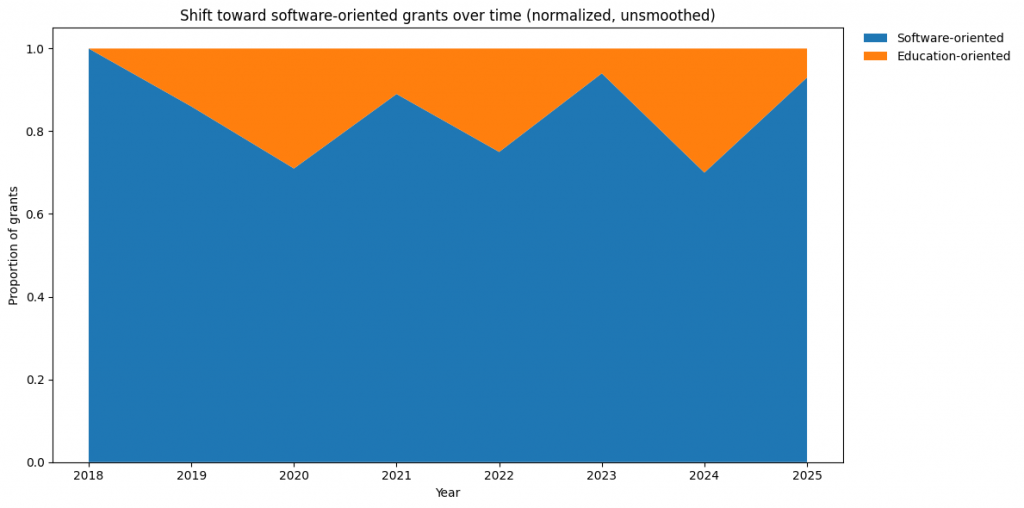

Across the full dataset, infrastructure holds roughly 82% of funding on average, while education commands about 18%. Education appears in 2019 and thereafter cyclically, rising sharply in 2020, 2022, and 2024. It never exceeds one‑third of annual funding.

| Year | Infrastructure | Education |

| 2018 | 100.0% | 0.0% |

| 2019 | 71.4% | 28.6% |

| 2020 | 72.2% | 27.8% |

| 2021 | 89.5% | 10.5% |

| 2022 | 69.2% | 30.8% |

| 2023 | 95.7% | 4.3% |

| 2024 | 68.2% | 31.8% |

| 2025 | 88.9% | 11.1% |

This pattern points to a practical constraint: a researcher can only work on a limited number of projects at any time. Long‑term progress therefore depends less on how much any one person can do and more on how many people are able to participate at all. Education becomes a bottleneck. Without sustained training, awareness, and onboarding, the infrastructure layer can’t grow fast enough to absorb new ideas.

Programs like Q‑CTRL’s Black Opal and IBM’s Qiskit Certification show how education can be treated as infrastructure. They lower entry barriers, create structured learning paths, and turn non‑quantum engineers into contributors. Companies that invest in education don’t just expand the field, but also build future recruiting pipelines. If someone spends hundreds of hours learning through a specific platform, that brand becomes their reference point. Education shapes both capability and long‑term affiliation.

6. Common team structures in quantum computing projects

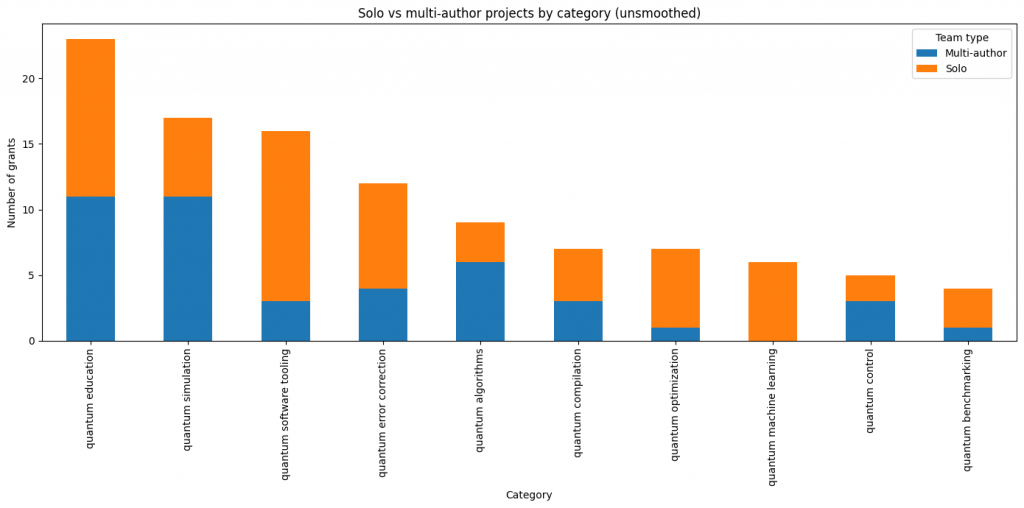

Solo and very small teams dominate the portfolio. Software tooling projects are 81.3% solo-authored. Optimization is even more individual at 85.7%. Quantum machine learning is entirely solo in this dataset.*

Collaboration appears where technical load increases. About 65% of simulation and algorithm projects are multi‑author. These areas demand verification, theoretical rigor, and performance validation, and benefit from shared review and division of labor.

| Category | Solo projects | Multi-author projects | Solo share | Multi-author share |

| Quantum education | 11 | 11 | 50.0% | 50.0% |

| Quantum simulation | 6 | 11 | 35.3% | 64.7% |

| Quantum software tooling | 13 | 3 | 81.3% | 18.7% |

| Quantum error correction | 8 | 4 | 66.7% | 33.3% |

| Quantum algorithms | 3 | 6 | 33.3% | 66.7% |

| Quantum machine learning | 6 | 0 | 100.0% | 0.0% |

| Quantum optimization | 6 | 1 | 85.7% | 14.3% |

| Quantum compilation | 4 | 3 | 57.1% | 42.9% |

| Quantum control | 2 | 3 | 40.0% | 60.0% |

| Quantum benchmarking | 3 | 1 | 75.0% | 25.0% |

* See the note in Section 8: Interdisciplinary activity on how we selected and categorized machine learning projects.

Median team sizes in quantum computing projects

| Output type | Median team size |

| Libraries | 1 |

| Simulators | 1 |

| Books | 1 |

| Education programs | 1 |

| Platforms | 2 |

| Compilers | 2 |

| Workshops | 4 |

| Integration projects | 4 |

This structure contrasts against the current economics of quantum hardware. Experimental devices require large laboratories, specialized facilities, and long capital cycles. Yet much of the foundational engineering that makes those systems usable is being built at a far lower cost by individuals and very small teams. Simulation frameworks, benchmarking tools, compilers, and libraries are advancing through work that is inexpensive financially but impactful structurally.

That creates a strategic opportunity. Companies building quantum hardware and platforms can accelerate progress by funding microgrants and small teams directly. This is both a way to expand the tooling ecosystem around their technology and a way to build a pipeline of researchers and engineers who understand the software layer deeply. Many of these builders come from non‑quantum backgrounds and enter through tooling, simulation, education, or infrastructure work. Microgrants therefore function both as an accelerator of technical progress and as a long‑range recruitment mechanism.

The data shows that a large share of meaningful progress in quantum engineering is occurring far below the cost profile of hardware itself. Small investments, placed widely, are producing durable components that shape how the field operates.

7. Quantum error infrastructure

Error infrastructure covers several distinct but connected strands:

- Quantum error correction focuses on encoding information so that faults can be detected and repaired.

- Quantum error mitigation aims to reduce the impact of noise without full correction, using statistical and algorithmic techniques.

- Quantum error characterization measures how devices behave in practice, building models of noise, drift, and instability.

- Benchmarking and validation sit alongside these, providing ways to compare systems and test whether methods work outside ideal settings.

Together, these strands define whether quantum systems can be trusted, not just demonstrated. In the dataset, error‑related work appears consistently but at low volume.

| Year | Share of projects focused on error infrastructure |

| 2018 | 11.1% |

| 2019 | 14.3% |

| 2020 | 11.1% |

| 2021 | 5.3% |

| 2022 | 7.7% |

| 2023 | 8.7% |

| 2024 | 27.3% |

| 2025 | 11.1% |

Only one year experienced reliability as a dominant theme: 2024. In every other year it remains secondary. This potentially reflects an ecosystem still centered on capability building rather than stabilization.

In the NISQ era, where noise defines the boundary of usefulness, stronger and more continuous investment in error infrastructure will shape how quickly experimental systems become dependable research tools.

8. Interdisciplinary activity in quantum computing

We define interdisciplinary activity as projects outside of core quantum computing like (information theory) and specifically aimed at another domain (like medicine). Our filtering shows interdisciplinary activity is present but narrow, with just four points of overlap with other domains:

Machine learning appears in 8* projects

Cryptography** appears in 2.

Medical imaging appears in 2.

Finance appears in 1.

More than 60% of all interdisciplinary work in the dataset touches machine learning. That’s not surprising, as machine learning shares tooling patterns, benchmarking culture, and performance‑driven experimentation with quantum computing.

What stands out is how thin the rest of the application landscape is. Finance appears only once. Medical imaging appears twice. Cryptography appears twice. This is a tiny signal given how strongly quantum computing is framed around these sectors in public and commercial narratives. Industry projections often place finance as one of the largest future users of quantum methods, yet it appears almost absent at the microgrant level.

Source: ”Embracing the Quantum Economy: A Pathway for Business Leaders” (World Economic Forum & Accenture) — January 2025

This all points to a structural bottleneck. Either there isn’t enough interest, not enough capability, not enough awareness, or not enough funding specifically aimed at applied crossover work. Targeted microgrants from financial institutions, healthcare companies, and security firms could change this quickly. These organizations are well placed to fund small exploratory projects that connect quantum methods to real domain problems, while also building internal understanding and early recruiting pipelines.

Notes:

* Though it was tagged in 15 projects in the dataset. Some projects would’ve fallen under multiple tags (e.g., quantum machine learning and quantum education), but we chose the strongest single category for easier analysis.

** Cryptography here is less about quantum cryptography (e.g., quantum random number generation) and more about post-quantum cryptography.

9. How microgrant funding in quantum computing can grow

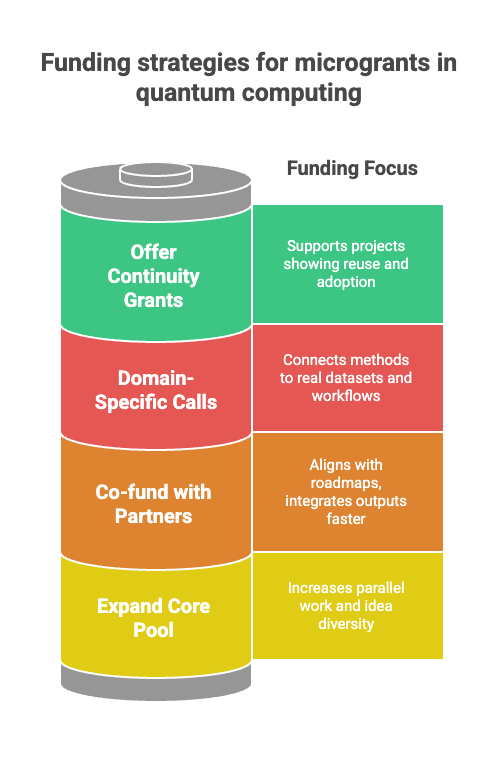

Microgrants scale best when they remain small per project but broad in reach. Growth is less about increasing individual grant size and more about increasing the number of funded experiments.

One path is to expand the core pool. Larger annual budgets allow more parallel work, which matters in a field where progress comes from many narrow tools rather than a few large programs. The advantage is speed and diversity of ideas. The risk is dilution of review capacity, which can be managed by rotating technical reviewers and tightening scope definitions.

Co‑funding with industry partners adds leverage. Hardware vendors, cloud providers, and software platforms can sponsor themed rounds that align with their technical roadmaps. The benefit is direct relevance and faster integration of outputs. The risk is bias toward sponsor priorities, which can be contained by preserving an independent allocation portion.

Domain‑specific calls create space for applied crossover work. Finance, health, energy, and security institutions can fund microgrants that connect quantum methods to real datasets and workflows. The benefit is early application literacy. The risk is shallow proofs of concept, which can be mitigated through staged funding.

Continuity grants support projects that show reuse and adoption. They prevent promising tools from stalling after initial release.

Measurement can track reuse rates, GitHub adoption, citation in research, downstream funding, and contributor retention. These metrics capture ecosystem impact better than publication counts alone.

10. Closing outlook on quantum computing microgrant funding

The Unitary Fund’s microgrant dataset shows a field being assembled in public: real work done by real people under tight constraints. One hundred and twenty‑nine projects over eight years isn’t a massive volume by industrial standards, but for a technology this young, it’s a meaningful body of infrastructure.

What stands out is how much progress is happening at low cost. Compared to the capital required to build quantum hardware, the software, tooling, and education layers are advancing through relatively small investments. That’s an opportunity for the industry. It means progress doesn’t only belong to large labs or national programs, but to anyone willing to fund careful, focused technical work.

The ecosystem doesn’t need fewer experiments. It needs more of them, spread across more domains. Finance, health, security, energy, and policy should all be visible at this layer.

Microgrants work because they trust that builders and small teams can produce durable infrastructure. Extending that trust, expanding the pool of funding, and widening the range of application domains is how quantum computing can move from promise to practice.

Appendix: Methodology

We analyzed 129 microgrant-funded projects awarded by the Unitary Fund between 2018 and 2025. We treated each project as one observation. When a project listed more than one country, we expanded the country field so every country received its own entry. That lets us measure participation rather than ownership and avoids undercounting international collaboration.

We used the primary category assigned to each project for all category-level analysis. When we needed a higher-level view, we collapsed categories into two groups: education and infrastructure. Education includes books, courses, workshops, outreach tools, and learning platforms. Infrastructure includes libraries, simulators, compilers, benchmarking tools, decoders, emulators, and research frameworks.

We separated technical categories from output types. A project could belong to a category like simulation or error correction while producing a library, platform, or book. That separation lets us describe both what people work on and what they actually build.

We measured team size using the number of listed contributors per project. We used medians instead of averages so a few large collaborations wouldn’t distort the picture. We calculated solo versus multi-author splits inside each category to understand how collaboration patterns vary across technical domains.

For interdisciplinary activity, we searched project descriptions for references to machine learning, cryptography, finance, and medical imaging. We used this as a directional signal rather than a precise classification.

To measure how diversified each country’s activity is, we used entropy. Higher entropy means work is spread more evenly across categories. Lower entropy means specialization. All statistics in this report are descriptive, used to observe structure and not to claim causation.

About the author

Mo Shehu, PhD is a researcher, and technical strategist working at the intersection of technology, policy, and public understanding. He has a background in informatics and analytics, and his work focuses on translating complex technical systems into structural insight. His research and writing examine how ecosystems form, how incentives shape technical behavior, and how early-stage infrastructure determines long‑term outcomes.

About Column

Column is a technical communications agency that helps technical organizations explain their work, position their ideas, and shape how emerging fields are understood. It produces research reports, policy briefs, thought leadership, and data‑driven analysis for technology, science, and public‑interest clients.

Mo is the founder of Column, a technical research and content agency. Connect with him on LinkedIn.